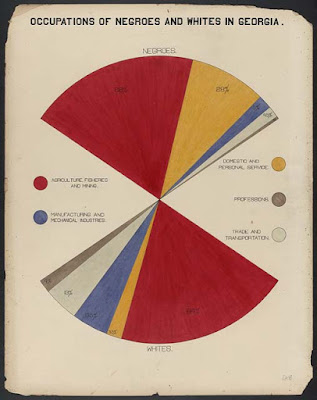

Negro Exhibition Diagram, 1900 Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Souls of Black Folk is now available in so many different editions that it is impossible to keep track of them all plus their various additions to the text but The Illustrated Souls of Black Folk edited and annotated by Eugene F. Provenzo Jr. is a particular favorite of mine because of its use of photographs and other materials stemming from The Negro Exhibition, which Du Bois compiled for the Paris Exposition of 1900.

Du Bois's purpose was to document for the world the economic and educational advances African Americans had made since their Emancipation from slavery in the United States of America. That Du Bois used photography the way he did at the turn-of-the century had much to do with recent advances in the technology of photography and its popularization via the blossoming popular culture of world's fairs and the related media of the illustrated press, journalism, postcards and film.

Cameras and the film needed to produce photographs were becoming increasingly accessible in middle class and working class communities. Providing the services of a photographic studio where one could purchase a portrait of oneself or of one's family was becoming a popular business in urban black communities as well as in cities all over the world of every description.

These photographs Du Bois commissioned and compiled of black businesses, black churches, black schools, and their occupants were the beginning of a trend in African American popular culture that would continue from the turn-of-the-century through the 1960s. As other media would increase in popularity in mainstream American culture, photography would not be displaced in black communities until much later because blacks had significantly less access to the mainstream of popular culture as represented by the corporatization of film, television, publishing and the mainstream press.

These photographs Du Bois commissioned and compiled of black businesses, black churches, black schools, and their occupants were the beginning of a trend in African American popular culture that would continue from the turn-of-the-century through the 1960s. As other media would increase in popularity in mainstream American culture, photography would not be displaced in black communities until much later because blacks had significantly less access to the mainstream of popular culture as represented by the corporatization of film, television, publishing and the mainstream press.

Only since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s have blacks had even hypothetical access to "mainstream" media. What they had instead was a separate press, separate towns, schools, and a largely separate (but not equal) popular culture, albeit in all aspects of performance, particularly musical performance. Ironically, with the success of the Civil Rights Movement came the collapse of much of this separate culture. As is common with popular culture generally, a lot of it has been lost without documentation partly because little value had been placed on it before.

With the rise of a computer technology and the internet, the possibility of making available to researchers generally the record that does survive has intersected with the rise of an audience which values these materials.

Among the textual materials supplementing Souls in Provenzo's version are:

Among the textual materials supplementing Souls in Provenzo's version are:

1) "The Emancipation Proclamation"

2) "An Act to Establish a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees"

3) Booker T. Washington's "Atlanta Exposition Speech" (a portion of which is included on the spoken word cd)

4) Du Bois's essay "The Talented Tenth"

5) Booker T Washington's "Nineteenth Annual Report of the Principal of Tuskeegee Normal and Industrial Institute"

6) Ida B. Wells' "Tortured and Burned Alive"; "

7) Du Bois's Atlanta University Report on "The Negro in the Black Belt"

8) Du Bois Crisis editorial "Colored Men Lynched Without Trial"

9) Selections from Du Bois' The Philadelphia Negro10) Thomas Wentworth Higginson's "Negro Spirituals"

The quality of illustration is very poor but the choices are interesting and instructive at least to me, never having had minimal access to any of this material prior to the rise of the internet and the two years I spent at Cornell University as a Visiting Professor, which gave me my first real access as an insider to a world class research library since the time I briefly spent in the early 80s at Yale University.

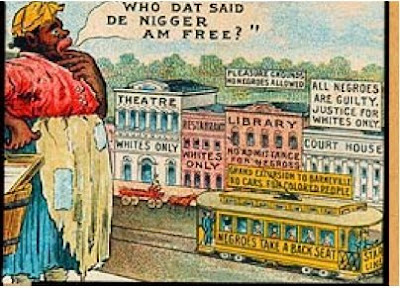

Provenzo reproduces via photocopy some of the actual pages of Du Bois's exhibition, some actual images and photographs taken from the pages of The Crisis, the journal Du Bois created under the auspices of the NAACP founded in 1906. Provenzo also includes sheet music covers, political cartoons and illustrations, and 19th century photographs taken from publications dealing with topics discussed in The Souls of Black Folk.

The quality of illustration is very poor but the choices are interesting and instructive at least to me, never having had minimal access to any of this material prior to the rise of the internet and the two years I spent at Cornell University as a Visiting Professor, which gave me my first real access as an insider to a world class research library since the time I briefly spent in the early 80s at Yale University.

Provenzo reproduces via photocopy some of the actual pages of Du Bois's exhibition, some actual images and photographs taken from the pages of The Crisis, the journal Du Bois created under the auspices of the NAACP founded in 1906. Provenzo also includes sheet music covers, political cartoons and illustrations, and 19th century photographs taken from publications dealing with topics discussed in The Souls of Black Folk.

Professor Eugene Provenzo is also the author of a particularly useful reconstruction of the Negro Exhibition online at http://www.education.miami.edu/ep/Paris/home.htm. As he notes although much of the material contained in the Exhibition are available in the photo archives of the Library of Congress there are some missing pieces.

Wiliam Edgar Burghhardt Du Bois, "The American Negro at Paris." The American Monthly Review of Reviews, Vol. XXII, New York, November 1900, #5, pp. 575-577.