This Fall I am teaching an undergraduate class on Toni Morrison with 80 students and a graduate class with 20 students at the City College of New York. Doing so has become a totally absorbing activity as I have been struggling to catch up with the brilliant proliferation of scholarship and media on the topic of Toni Morrison and her writings at the same time that I am keeping up with 100 students.

We are reading four books in the following order: The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, Beloved and Jazz. As we are entering the middle section of the semester, I would completely change the order if I could. I think perhaps now it would have been good if we had read Jazz first. Just jump into the deep end of the pool, into the heart of Morrison's work, from the very beginning. Also, I think I would have liked to have included at least one of the 3 most recent books. Perhaps the most likely choice would be Home although Love might have served just as well. All of the books shed light on all the other books so there are many combinations that might suggest themselves. Of course, the very best would be to do the class in which the students would read all ten of her novels, or at least 8 of them. But I think the books are best understood in the light they shed upon one another.

In any case, am going to include here to 2 links to videos of a conference on the religious dimensions in Toni Morrison's work which occured at the Harvard Divinity School. One link is to the lecture that Morrison gives on the theme of Mercy. The conference which features faculty expounding on the sermon in various Morrison novels will be the first link. I would direct your attention in particular to the extraordinary comments of Reverend Jay Williams on the sermon by Pilate in Song of Solomon. I cannot help but add my frustration in not being able to stream this material in my classroom at the City College of New York because our internet strength is not great enough to support such a practice. I have managed to make an audio tape of William's remarks to present in class today I hope although I am not sure of the sound quality.

10/17/13

Toni Morrison: Lord Have Mercy

Labels:

Beloved,

Christianity,

Harvard Divinity School,

Jay Williams,

Jazz,

Mercy,

Song of Solomon,

Toni Morrison

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

Have Mercy: The Religious Dimensions of the Writings of Toni Morrison (+...

Labels:

Christianity,

Harvard Divinity School,

Mercy,

the Amish,

Toni Morrison

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

Goodness: Altruism and the Literary Imagination (+playlist)

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

11/22/12

The Lincoln Film: Not For The Masses, Really?

|

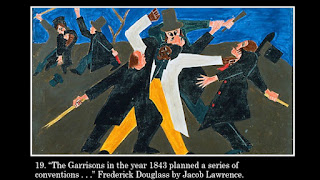

| Painting from Frederick Douglass Series (1939) by African American Artist Jacob Lawrence. Copyright restricted. See http://www.jacobandgwenlawrence.org/artandlife04.html |

There are many things that struck me as extremely relevant to our current curriculum. It helps in this case to read some of the better reviews, which may help to draw your attention to the more important historical features. I will make a folder of some of the links and place them among your course materials.

In regard to the first question I posed, that is whether it would be a reconciliationist, white supremacist or emancipationist version of the Civil War, it seemed to me that the film touched equally upon all three and ultimately did not resolve itself in favor of any of the three. In this sense, it was a fascinatingly wise contemplation on the legacy of the life of Abraham Lincoln, the conclusion of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment. But if I had to choose one, I would choose emancipationist in the sense that everything in the film pointed my thoughts to the future we actually live in, in which we have now a black president who is having as much trouble getting change through Congress as Lincoln had in having the 13th Amendment passed.

The film is about the difficulty of the political process as it occurs in a republic in which freedom of thought and word is a founding assumption. In the scene near the end of the film in which Thaddeus Stevens and his mistress Lydia Davis are reading the 13th Amendment in bed, this is where D.W. Griffith's white Supremacist film The Birth of a Nation (1915) actually begins. Both Stevens and Davis are horribly caricatured in his film and portrayed as monsters determined to destroy the country and the white majority in favor of the mongrel ambitions of miscegenation and racial mixing. Lydia in particular is demonized. It seems all the more fitting that Spielberg's film would end with Lydia humanized by the sensible acting of Epatha Merkinson, whom we have all known so many years from Law and Order. I don't think the part is big enough for an actual nomination but I wish it were.

As for the reconciliationist perspective of a film such as Gone With The Wind (1939), the profound depth and tenderness of the mature relationship between Lincoln and his wife Mary seems to mock the trivial superficiality of such a treatment of the Civil War and hits consequences. Abraham and Mary's contrast with Rhett and Scarlett couldn't be greater or more revealing.

What makes it such a great lesson for all of us is that it brings the legislation we have been studying vividly to life. I don't think you can come away from watching this film without becoming completely cognizant of what the 13th Amendment achieved (the abolition of slavery), or how it differed from the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as its limitations and ultimately the necessity for both the 14th (citizenship) and the 15th (the vote)Amendment. What is forecast as well, it seems to me, is that none of this legislation would finally succeed in transforming the former slaves into fully recognized and fully participant American citizens.

The portrayal of events takes for granted the omniscience of white supremacy at the time. The very fact that Congressman Thaddeus Davis, who is in a relationship with a black woman to whom he takes the rough draft of the amendment to read to her in bed, is forced to renounce his own beliefs in racial equality on the floor of the congress in order to get the 13th amendment passed clarifies the hegemony of white supremacy at the time. Nonetheless, it further embellishes one's enjoyment of these events if one knows what will follow--as you can easily find out by reading, first of all, the second chapter of W.E.B. Du Bois's The Souls of Black Folk (which you have already been assigned to do), not to mention as well the Reconstruction Wiki I assigned you.

Which brings me to the only disappointment I felt in this film and that is that there are no roles for blacks large enough to get your teeth into, not even that of Nancy Keckley who was Mary Lincoln's dressmaker and companion. All of the black roles--in particular the soldier in the beginning who completes the recitation of the Gettysburg Address as he wanders off into the night--are lovely and beautiful but they are not allowed to take on important dramatic depth and substance. Perhaps it wouldn't be appropriate to this portion of the history, the month or so preceding the murder of Lincoln, and it seems petty in the end to quibble about this one shortcoming when so many other films in which black actors are featured have none of the pluses of this beautifully and densely written script, but it is hard to believe that this isn't an important consideration. If it isn't important, why not have the densely written black character instead of not?

To which I have two perhaps contradictory answers. First, part of the reason it is this way is because of the evils of the star system, and the fact that the name brand combination of the package takes precedence over whatever magic the script and the performance are able to produce. It's got to be an exciting package from the marketing point of view. Nothing else matters. Even so I can't imagine that this film will do particularly well at the box office but it should do very well indeed among the awards.

Just look at the content of the advertising, the focus on the tortured face and figures of the stars--Daniel Day Lewis and Sally Fields--both wonderful but without their former reputations as actors, they would not be able to occupy these roles. Not as unknowns. Which also means the following. First of all no black woman could be given a major role. Black actresses just aren't there yet. Not even Haile Berry. Not even Vanessa Williams. Rather it would have to be a black male with a major name, and such a man (Denzel Washington or Sam Jackson or somebody like that) would never take the lesser role that such a part would likely be. A major black male role would be in danger of completely derailing the subtle balance of the current script. This film is not about the freedom or the equality of women or of blacks, but rather a moment still pregnant with that possibility.

At the same time, the racial equilibrium of this script speaks to the ongoing power of white supremacy in our culture, to the fact that we still don't know how to imagine what kind of moral and aesthetic hierarchy might actually follow. That just like Lincoln and his most well intentioned contemporaries we still don't know quite how to incorporate the agency of actual black people (and former slaves) into the mainstream of the story we tell ourselves about the history of our country and our culture.

Labels:

13th Amendment,

Abraham Lincoln,

Frederick Douglass,

Gone With the Wind,

Jacob Lawrence,

Lydia Davis,

Thaddeus Stevens,

The Birth of a Nation,

the Civil War,

The Souls of Black Folk,

WEB Du Bois

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

8/16/12

Langston Hughes's Ask Your Mama!

-->

-->

12 Part

epic poem with musical cues drawn from the blues, New Orleans Jazz, Gospel,

Boogie Woogie, BeBop and other forms of progressive jazz written by Langston

Hughes in the early 60s.

It was

never performed in his lifetime but Dr. Ron McCurdy has a production of it

online at the following addresses.

The politics of this piece are fascinating. I can well imagine it being performed at the a Newport Jazz

Festival in the early 60s sandwiched between Louis Armstrong and Duke

Ellington.

Contemporary

Performance of Ask Your Mama!

The

Langston Hughes Project: Descriptions of Ask Your Mama!

Labels:

Ask Your Mama,

Langston Hughes

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

8/14/12

David Blight on Slavery and Reconstruction on YouTube

David Blight's "The Civil War and Reconstruction," an Open course offered via Yale University's website, via YouTube and via itunes unversity audio and visual files provides a compelling and detailed description of the events and the debates precipitated by the American Legacy of the Civil War and Slavery. http://oyc.yale.edu/history/hist-119#sessions

His lectures bring back my fond days as a graduate student in American Studies at Yale University and the opportunity to hear the lectures of historians John Blassingame, Edmund Morgan and David Brion Davis among others. Two years after the publication of my first book (in which slavery is discussed in some detail) in 1980 and 1981, I got my first real chance to study slavery and its consequences in a serious way in a world class library system--via access to primary sources, and the very best of secondary sources, and moreover to learn to know the difference.

Listening to his descriptions of the scholarship of Charles Beard as a progressive historian who saw slavery and the free north as two competing economic systems caused me to recollect that in 11th Grade at the New Lincoln School, we read Charles Beard and Walt Whitman as part of our core curriculum on American history and literature.

I couldn't quite get my fingers around this approach, was somewhat hurt and confused by it. So much else was going on in my life and my body (I was 15) and there's a particular way in which your mind can wander when you are a teenager in a classroom. and I remember being frustrated by the lack of talk about the slaves or even abolitionism. My teacher that year was named Mac Carpenter. I wish I had had Beisel and Moby Dick (a book I would learn to love some ten years later) instead but had been turned off by the idea that a book about a whale wouldn't be girly enough. I had no idea who I was then.

Nonetheless, I have continued to follow the fields of American slavery and abolitionism, as well as the new scholarship on the transatlantic slave trade with the maps and ship manifests. I just love all that stuff. My reading in these areas comes out of a true passion for the subject matter and the writing in this field, rather than as a necessity of my teaching. It has been my good fortune for my study to have occurred during the period of the greatest development in this field of study. Blight's lectures are a product of this development of study, highly listen-able, and providing as good a beginning as any to the field--knowledgeable regarding the latest transatlantic and colonial scholarship and yet (as he might say) firmly rooted in a deeply Americanist perspective.

-->

His lectures bring back my fond days as a graduate student in American Studies at Yale University and the opportunity to hear the lectures of historians John Blassingame, Edmund Morgan and David Brion Davis among others. Two years after the publication of my first book (in which slavery is discussed in some detail) in 1980 and 1981, I got my first real chance to study slavery and its consequences in a serious way in a world class library system--via access to primary sources, and the very best of secondary sources, and moreover to learn to know the difference.

Listening to his descriptions of the scholarship of Charles Beard as a progressive historian who saw slavery and the free north as two competing economic systems caused me to recollect that in 11th Grade at the New Lincoln School, we read Charles Beard and Walt Whitman as part of our core curriculum on American history and literature.

I couldn't quite get my fingers around this approach, was somewhat hurt and confused by it. So much else was going on in my life and my body (I was 15) and there's a particular way in which your mind can wander when you are a teenager in a classroom. and I remember being frustrated by the lack of talk about the slaves or even abolitionism. My teacher that year was named Mac Carpenter. I wish I had had Beisel and Moby Dick (a book I would learn to love some ten years later) instead but had been turned off by the idea that a book about a whale wouldn't be girly enough. I had no idea who I was then.

Nonetheless, I have continued to follow the fields of American slavery and abolitionism, as well as the new scholarship on the transatlantic slave trade with the maps and ship manifests. I just love all that stuff. My reading in these areas comes out of a true passion for the subject matter and the writing in this field, rather than as a necessity of my teaching. It has been my good fortune for my study to have occurred during the period of the greatest development in this field of study. Blight's lectures are a product of this development of study, highly listen-able, and providing as good a beginning as any to the field--knowledgeable regarding the latest transatlantic and colonial scholarship and yet (as he might say) firmly rooted in a deeply Americanist perspective.

-->

Knew him first by his book Race and Reunion: The Civil War

in American Memory, which I encountered via my grad student (presently Professor of African American Studies at Lehman College) Anne Rice. Then a few years later I

shared a stage with him on D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation at the New

School but it was a crowded program and I can't recall what he said at all. I tried to talk about the music which was written for the movie. I still had him pegged as someone who was much more interested in the contemporary consequences of the Civil War.

The next time was my discovery that David Blight was a Professor of History at Yale University via this series of lectures on

slavery and reconstruction offered as part of Open University online, based on a

year long course as taught at Yale University in 2007.

I fell in love with it not because I agreed with and

celebrated each word, but rather because of its thoroughness, its simplicity

and clarity, its fascination with the literature produced by former slave and

white Americans, its intensity, its contextualization of abolitionism within the larger context of the myriad causes of Civil War. His

is not the African American perspective, which has been a major influence in

slavery scholarship in the past few decades. And it isn’t the White Southern perspective either, which seems to me

the focus of the Ken Burns’ documentary version of the Civil War and that of the Civil War re-enactors Blight

describes in his book on the topic.

But rather this is finally an accessible Americanist and centrist re-telling of the many stories that make up

this great war and its immediate consequences, especially in regard to the Reconstruction Era.

His delivery is stunningly and entertainingly folksy at times but not Southern folksy, maybe

rather mid-Western folksy to the degree that it becomes part of the content. What better voice could one find to

represent the collective madness that descended upon the American republic

(as its borders spread West) mid-19th century and resulted in the collective genocidal impulse Americans visited upon

themselves in the form of its Civil War.

I will attempt to make selections from specific lectures to sample in my classes and to

illuminate the content of my courses on “Slavery and the Failure of

Reconstruction” as a FIQWS and my World Humanities course 102.

Labels:

David Blight,

Frederick Douglass,

Reconstruction,

Sheridan's Ride,

Slavery,

The Birth of a Nation,

the Civil War

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

Clayborne Carson, Stanford University Historian

This link leads to my comments on Clayborne Carson's lecture series on itunes and youtube on the Black Freedom Struggle. I have gathered all the lectures together on my YouTube Channel under the name of Olympia2X.com, Blues People.

I will be excerpting for my hybrid class (African American Literature: 1930s thru 1960s) the first two lectures on WEB DuBois, the third lecture on DuBois's second (or was it third?) wife, Shirley Graham, who apparently wrote and produced one of the first African American operas written and composed by an African American (something I am just finding out. Sadly it looks like copies of this opera exist only perhaps among her personal papers at Radcliffe). Also, I will refer to Lecture 12 in which Carson deals with Malcolm X, and brings to it the insights he must have gained in part from editing Malcolm X: The FBI Files (1991).

http://blackmachorevisited.blogspot.com/2012/08/clayborne-carson-lectures-in-2007-on.html

Labels:

Claybourne Carson,

Malcolm X,

Shirley Graham,

WEB Du Bois

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

6/4/12

The Cartography of Slavery

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/12/10/opinion/20101210_Disunion_SlaveryMap.html

This is the more interactive version provided by the NY Times. One of the most important maps of the Civil War was also one of the most visually striking: the United States Coast Survey’s map of the slaveholding states, which clearly illustrates the varying concentrations of slaves across the South.

This is the more interactive version provided by the NY Times. One of the most important maps of the Civil War was also one of the most visually striking: the United States Coast Survey’s map of the slaveholding states, which clearly illustrates the varying concentrations of slaves across the South.

Labels:

Birth of a Nation,

Slavery,

the Civil War

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

New York Underground

The subject of the New York Underground is connected to the subject of Blues People and their culture via the short story by Richard Wright, The Man Who Lived Underground, which follows the actions of an African American male fleeing from the police accused of a crime he did not committ into the sewers where he begins to have a different kind of life in which his consciousness is altered and his fears cease to exist.

Of course, his plight is a tragic one. Studying this site constructed by National Geographic which gives lots of information and illustrations concerning the construction and the history of the distribution of power and water underground, it is not surprising that things don't turn out well for the underground man. Along with the wires and the pipes, he is part of the underbelly of the city. This is a great website providing a lot of information and illustration of how the underground of New York is currently constructed. A good thing to know should the need arise.

Of course, his plight is a tragic one. Studying this site constructed by National Geographic which gives lots of information and illustrations concerning the construction and the history of the distribution of power and water underground, it is not surprising that things don't turn out well for the underground man. Along with the wires and the pipes, he is part of the underbelly of the city. This is a great website providing a lot of information and illustration of how the underground of New York is currently constructed. A good thing to know should the need arise.

New York Underground, the page is called and sponsored by National Geographic at http://www.nationalgeographic.com/features/97/nyunderground/docs/nymain.html.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

5/5/12

Black Reconstruction--W.E.B. Du Bois

"Here is the real modern labor problem. Here is the kernel of the problem of Religion and Democracy, of Humanitty. Words and futile gestures avail nothing. Out of the exploitation of the dark proletariat comes the Surplus Value filched from human beasts which, in cultured lands, the Machine and harnessed Power veil and conceal. The emancipation of man is the emancipation of labor and the emancipation of labor is the freeing of that basic majority of workers who are yellow, brown and black." (16)

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of hte Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. Atheneum (1935) 1973

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of hte Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. Atheneum (1935) 1973

Labels:

Reconstruction,

Slavery,

the Civil War,

WEB Du Bois

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

4/16/12

Life Upon These Shores

Labels:

Henry Louis Gates,

Jr.,

Slavery,

the Civil War

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

12/4/11

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

Dear Students: I forgot to mention two things in class, which came up on your papers on your prior reading of the literature of African American slavery.

First, some students listed Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, which is not a work of African American Literature and does not deal with African American slavery (although there are some incidences of internal slavery). Things Fall Apart is an African novel, the first really important one published in English. Achebe is Nigerian Ibo and portrays life before and during British colonialism in his part of the work. Although the novel is fictional, it is nonetheless set in the historical context of the turn of the century. Achebe wrote it in part in response to Joseph Conrad's portrayal of Africa in Heart of Darkness, which at least one other person mentioned in our survey of African American Literature. Of course, Heart of Darkness isn't African American Literature either.

It is written by Joseph Conrad in 1903 (the same time as Souls of Black Folk) and it deals with the Congo (Central Africa), which was at the time a private and illegal colony of Belguim's King Leopold II (one of the scariest of the European colonial interlopers on the African continent). Conrad is Polish (not African, not African American) as I recall and his story is both symbolic and fictional. Nonetheless, he does a good job of capturing the hopelessness and despair of the Congo for its inhabitants at the time.

Both books are extremely important and bear upon the colonialism and imperialism visited upon the African continent pretty much as an adjunct to the period during which millions of slaves were transported to the New World in the African slave trade. It was yet another way of exploiting the continent's riches, but with little historical overlap. African American slavery ends in the last of the New World colonies in the 1890s, at the same time that the so called "Scramble for Africa" begins in earnest among a number of Western European nations in which they divide up the largely undeveloped terrain of the African continent--North, South, East and West--between themselves. It was possible to do this without necessarily consulting the inhabitants or the existing infrastructure (the way Achebe describes it in Things Fall Apart) and much as Americans and Europeans divided the Americas without reference to the existing infrastructure of the Native American tribes already on the land.

Sometimes they briefly negotiated with and managed the tribes. Alternatively, Other times in an extremely helter skelter fashion, they massacred them. One mode of almost certainly resulting in random violence skirmishes and ultimately genocide would be to open up a piece of land to American or European settlement. Such pioneers would rush in to claim their plot, and deal without whatever or whoever got in their way. They were always armed and they were brainwashed to considered the current inhabitants of the land as savages and inferior beings, like the buffalo.

Anyhow there are some interesting connections here. Hope this helps. Thanks.

First, some students listed Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, which is not a work of African American Literature and does not deal with African American slavery (although there are some incidences of internal slavery). Things Fall Apart is an African novel, the first really important one published in English. Achebe is Nigerian Ibo and portrays life before and during British colonialism in his part of the work. Although the novel is fictional, it is nonetheless set in the historical context of the turn of the century. Achebe wrote it in part in response to Joseph Conrad's portrayal of Africa in Heart of Darkness, which at least one other person mentioned in our survey of African American Literature. Of course, Heart of Darkness isn't African American Literature either.

It is written by Joseph Conrad in 1903 (the same time as Souls of Black Folk) and it deals with the Congo (Central Africa), which was at the time a private and illegal colony of Belguim's King Leopold II (one of the scariest of the European colonial interlopers on the African continent). Conrad is Polish (not African, not African American) as I recall and his story is both symbolic and fictional. Nonetheless, he does a good job of capturing the hopelessness and despair of the Congo for its inhabitants at the time.

Both books are extremely important and bear upon the colonialism and imperialism visited upon the African continent pretty much as an adjunct to the period during which millions of slaves were transported to the New World in the African slave trade. It was yet another way of exploiting the continent's riches, but with little historical overlap. African American slavery ends in the last of the New World colonies in the 1890s, at the same time that the so called "Scramble for Africa" begins in earnest among a number of Western European nations in which they divide up the largely undeveloped terrain of the African continent--North, South, East and West--between themselves. It was possible to do this without necessarily consulting the inhabitants or the existing infrastructure (the way Achebe describes it in Things Fall Apart) and much as Americans and Europeans divided the Americas without reference to the existing infrastructure of the Native American tribes already on the land.

Sometimes they briefly negotiated with and managed the tribes. Alternatively, Other times in an extremely helter skelter fashion, they massacred them. One mode of almost certainly resulting in random violence skirmishes and ultimately genocide would be to open up a piece of land to American or European settlement. Such pioneers would rush in to claim their plot, and deal without whatever or whoever got in their way. They were always armed and they were brainwashed to considered the current inhabitants of the land as savages and inferior beings, like the buffalo.

Anyhow there are some interesting connections here. Hope this helps. Thanks.

Labels:

Chinua Achebe,

Nigeria,

Scramble for Africa,

Slavery

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

12/1/11

Dubois Concerning Black Music

Overwhelmingly the mass of writings on African American music have been written about music produced in the 20th century owing to the importance of the invention of recorded sound as a reliable object of study. However most studies which include discussion of early African American music and its religious inflections will include some speculation on its relationship to slavery, Reconstruction and the semi-freedom of the Jim Crow Period.

In the further pursuit of materials related to Du Bois discussion of the development of the music of the slaves in Chapter 10 "Faith of Our Fathers" and in his final chapter on the Sorrow Songs in The Souls of Black Folk, the following crucial texts come highly recommended by me:

Dena J. Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. University of Illinois Press 1977.

Shane White and Graham White, The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering African American History through Songs, Sermons and Speech. Beacon Press 1992.

Robert Darden, People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Continuum 2004.

Michael W. Harris, The Rise of the Gospel Blues: The Music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Church. Oxford University Press 1992.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, If You Don't Go, Don't Hinder Me: The African American Sacred Song Tradition. University of Nebraska Press 2001.

Eileen Southern, Readings in Black American Music. Second Edition, Norton Press 1983.

In the further pursuit of materials related to Du Bois discussion of the development of the music of the slaves in Chapter 10 "Faith of Our Fathers" and in his final chapter on the Sorrow Songs in The Souls of Black Folk, the following crucial texts come highly recommended by me:

Dena J. Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. University of Illinois Press 1977.

Shane White and Graham White, The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering African American History through Songs, Sermons and Speech. Beacon Press 1992.

Robert Darden, People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Continuum 2004.

Michael W. Harris, The Rise of the Gospel Blues: The Music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Church. Oxford University Press 1992.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, If You Don't Go, Don't Hinder Me: The African American Sacred Song Tradition. University of Nebraska Press 2001.

Eileen Southern, Readings in Black American Music. Second Edition, Norton Press 1983.

Labels:

Gospel,

Slavery,

Spirituals,

the Civil War,

WEB Du Bois

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

11/27/11

Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World

"Since Europeans in every region were enslaved in Roman and early medieval times (to say nothing of Asia and Africa, and since Barbary corsairs continued to enslave white Europeans and Americans well into the nineteenth century) it seems highly probable that if we could go back far enough in time, we would discover that all of us reading these words are the descendants of both slaves and masters in some part of the world. It was not until the seventeenth century that even New World slavery began to be overwhelmingly associated with people of black African descent—as opposed to Native Americans."

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World Oxford UP 2006 (54)

Masterful work of one of the most brilliant historians of comparative slavery in the world. Briefly my teacher at Yale University, I am proud to say.

Labels:

David Brion Davis,

Slavery,

the Civil War

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

11/14/11

Of The Dawn of Freedom

Trying to remember how I first came to Dubois. I know it was after I went to Yale, and the year my own book came out (Black Macho and The Myth of the Superwoman) in 1979.

Knowing so little then of Dubois and the Souls of Black Folk (a foundational work in the Afro American intellectual tradition)I guessed was what people meant when they said I was too ignorant to have written a book diagnosing the problems of black gender politics in the 1960s and 1970s.

It is certainly true that when I wrote Black Macho, I knew virtually nothing of the Ivy League or the HBCUs, nor the many gifts they had shared with one another, black and white sisters and brothers. But then I encountered Robert Stepto's book Beyond the Veil, which came out the same year as Black Macho. This book was the beginning of a coherent and theoretical Afro American literary critical discourse for me and a lot of other people. He built his theory of an African American literary canon around "The Souls of Black Folk."

*****

"Of the Dawn of Freedom" is the title of the second chapter of W.E.B. Du Bois' celebrated masterpiece Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois tells the story of Reconstruction as rarely heard in 1903, and at least as little known in 2011. I have heard it said that Souls of Black Folk is too conventional and difficult text for our time but I find it difficult to imagine how one can be adequately introduced to the disappointments and horrors of Federal Reconstruction, particularly for the first time, in a better manner.

This chapter is a work of poetry at the same time that reading it can leave no doubt as to what the problems were, why Reconstruction failed. Du Bois makes it clear, it failed because it did not go nearly far enough. It did not go nearly far enough because of bitterness and racism that loomed over the newly freed slaves in the wake of the Civil War.

The chapter begins and ends with exactly the same sentence as if to represent a hopeless and circular process: "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line . . ." It's a famous line often taken out of context and used to represent the importance and the depth of the entire book, as though this prediction in 1903 was the most important thing about the book, when in fact what the book communicates about the world that preceded 1903 is much more important than what it can tell us about the future.

But also the beauty of the book is first revealed in the poetry of this chapter in the passages in which Du Bois attempts to capture the misery and hopelessness of the former slaves, a picture he evokes from imagination since he was not yet born when the Civil War occured in the early 1860s.

Quotations from Chapter 2, Of The Dawn of Freedom--

The purposes of the Freedman's Bureau:

See lecture by Professor David Blight on Reconstruction at Yale University at the following link:

http://academicearth.org/lectures/black-reconstruction-economics-of-land-and-labor

Knowing so little then of Dubois and the Souls of Black Folk (a foundational work in the Afro American intellectual tradition)I guessed was what people meant when they said I was too ignorant to have written a book diagnosing the problems of black gender politics in the 1960s and 1970s.

It is certainly true that when I wrote Black Macho, I knew virtually nothing of the Ivy League or the HBCUs, nor the many gifts they had shared with one another, black and white sisters and brothers. But then I encountered Robert Stepto's book Beyond the Veil, which came out the same year as Black Macho. This book was the beginning of a coherent and theoretical Afro American literary critical discourse for me and a lot of other people. He built his theory of an African American literary canon around "The Souls of Black Folk."

*****

"Of the Dawn of Freedom" is the title of the second chapter of W.E.B. Du Bois' celebrated masterpiece Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois tells the story of Reconstruction as rarely heard in 1903, and at least as little known in 2011. I have heard it said that Souls of Black Folk is too conventional and difficult text for our time but I find it difficult to imagine how one can be adequately introduced to the disappointments and horrors of Federal Reconstruction, particularly for the first time, in a better manner.

This chapter is a work of poetry at the same time that reading it can leave no doubt as to what the problems were, why Reconstruction failed. Du Bois makes it clear, it failed because it did not go nearly far enough. It did not go nearly far enough because of bitterness and racism that loomed over the newly freed slaves in the wake of the Civil War.

The chapter begins and ends with exactly the same sentence as if to represent a hopeless and circular process: "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line . . ." It's a famous line often taken out of context and used to represent the importance and the depth of the entire book, as though this prediction in 1903 was the most important thing about the book, when in fact what the book communicates about the world that preceded 1903 is much more important than what it can tell us about the future.

But also the beauty of the book is first revealed in the poetry of this chapter in the passages in which Du Bois attempts to capture the misery and hopelessness of the former slaves, a picture he evokes from imagination since he was not yet born when the Civil War occured in the early 1860s.

Quotations from Chapter 2, Of The Dawn of Freedom--

***The war had naught to do with slaves, cried Congress, the President, and the Nation; and yet no sooner had the armies, East and West, penetrated Virginia and Tennessee than fugitive slaves appeared within the lines. They came at night, when the flickering camp-fires shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon; old men and thin, with gray and tufted hair; women, with frightened eyes, dragging whimpering hungry children; men and girls, stalwart and gaunt, --a horde of starving vagabonds, homeless, helpless, and pitiable, in their dark distress.

***Then the long-headed man with care-chiselled face who sat in the White House saw the inevitable, and emancipated the slaves of rebels on New Year's, 1863. A month later Congress called earnestly for the Negro soldiers whom the act of July, 1862, had half grudgingly allowed to enlist. Thus the barriers were levelled and the deed was done. The stream of fugitives swelled to a flood, and anxious army officers kept inquiring "What must be done with the slaves, arriving almost daily? Are we to find food and shelter for women and children?"

***Some see all significance in the grim front of the destroyer, and some in the bitter sufferers of the Lost Cause. But me neither soldier nor fugitive speaks with so deep a meaning as that dark human cloud that clung like remorse on the rear of those swift columns, swelling at times to half their size, almost engulfing and choking them. In vain were they ordered back, in vain were bridges hewn from beneath their feet; on they trudged and writhed and surged, until they rolled into Savannah, a starved and naked horde of tens of thousands. There too came the characteristic military remedy:

'The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice-fields about the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. John's River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of Negroes now made free by act of war." So read the celebrated 'Field-order Number Fifteen.'

The purposes of the Freedman's Bureau:

****Forthwith nine assistant commissioners were appointed. They were to hasten to their fields of work; seek gradually to close relief establishments, and make the destitute self-supporting; act as courts of law where there were no courts, or where Negroes were not recognized in them as free; establish the institution of marriage among ex-slaves, and keep records; see that freedmen were free to choose their employers, and help in making fair contracts for them . . .

See lecture by Professor David Blight on Reconstruction at Yale University at the following link:

http://academicearth.org/lectures/black-reconstruction-economics-of-land-and-labor

Labels:

David Blight,

Freedman's Bureau,

Reconstruction,

Slavery,

the Civil War,

The Souls of Black Folk,

WEB Du Bois

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

10/19/11

More Images by Jacob Lawrence on the Life of Frederick Douglass

Labels:

Frederick Douglass,

Jacob Lawrence,

Slavery

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

Frederick Douglass Series by Jacob Lawrence

Labels:

Frederick Douglass,

Jacob Lawrence,

Slavery

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

4/21/11

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself

|

| Harriet Jacobs (Linda Brent) at the time of the publication of her Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Written by Herself. http://www.harrietjacobs.org |

Among the readings this semester (Sp 2011), was included excerpts from "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself" by Harriet Jacobs. I suggested that students follow the materials as presented in The Norton Anthology of African American Literature (2nd Edition 2005 edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie McKay), which includes an explanatory essay about how and why Jacobs wrote her narrative under the pseudonym Linda Brent. Nonetheless, it was apparent to me in reading the midterms that students had gotten their texts helter skelter from a variety of online or used sources, some of which were probably written when some scholars still thought that the Jacobs narrative was a work of fiction and not written by a former black female slave.

Such work would not have recognized the important intervention literary historian Jean Fagin Yellin had made into our knowledge of Harriet Jacobs in 1987 in her admirable edition of the "Incidents" in which she draws upon the correspondence between Jacobs and Lydia Maria Child, who acted as her editor, and accompanies us through every detail of her escape. Since having altered the general understanding of the Jacob's narrative, the only slave narrative of a black woman actually written by herself, Yellin has further added to our knowledge publishing "Harriet Jacobs: A Life"(Basic Books 2004), and also completing the Harriet Jacobs Papers.

Despite her subsequent anonymity, Jacobs was not an obscure or isolated figure during the period in which "Incidents" was published. History had forgotten her but at the time she lived she was an active participant in the Abolitionist Movement, although she would have obviously been restricted to the female sphere. In the period in which she wrote her narrative (1861), the public lives of women were severely restricted by custom and by their lack of the franchise. Despite the dangers of a runaway slave being returned to her owner, Jacobs participated in the Abolitionist Movement in Rochester, New York where she worked in an antislavery reading room and bookstore just above the offices of Frederick Douglass's "North Star" newspaper. Yellin's scholarship substantiates that through her work as an ex-slave, she had an opportunity to meet and work with some of the most progressive women in Northern urban America.

Because of the nature of Jacob's narrative and the necessity for her including a confession of how she came to engage in pre-marital sex with a white man who was not her husband (the father of her children) but not her owner, her account poses a challenge to our comprehension of the sexual conventions and values of the 19th century South. We might reasonably wonder, as I did when writing about Jacobs in my first book "Black Macho and The Myth of the Superwoman," how could a slave be so concerned about preserving her sexual innocence? How did she ever come to be innocent in the first place in the context of slavery, which I was taught to regard as an ongoing brothel? But as Yellin helps us to better understand, the life of the slave was not monolithic and unvarying. As we learn from Douglass's narrative as well, slave children, depending upon whether they were born on a large or small plantation, owned by a large or small family and a variety of other factors, were sometimes gradually eased into the full comprehension of their plight as slaves. Until she successfully fled slavery, Jacobs had a family including a free grandmother, even though the families of the slaves were not recognized by law.

The importance of Jacob's story, which is obviously exceptional rather than typical of the conditions of the black female slave, is that we understand that enslavement was defined by the people who lived under it, not solely by the institution itself, which is part of what makes Yellin's narrative a work of literature worthy of our study and reflection.

Jean Fagin Yellin has painstakingly reconstructed Jacob's life and rounded up her correspondence for posterity. If she had not, we black women of the 20th century might not have ever realized the compelling authenticity of Jacob's story. Unfortunately, this doesn't mean that all of the editions which refer to her work as fictional and her narrative as unreliable are automatically barred from our library and bookstore shelves.

Labels:

Harriet Jacobs,

Slavery

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

12/11/10

Map of Slavery United States

Labels:

Slavery,

the Civil War

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

Bluesland: The Purpose of the Blues in this Class

|

| Blind Lemon Jefferson |

|

| Bukka White |

|

| Lead Belly |

|

| Langston Hughes's The Weary Blues |

This is not a music class and yet our primary reference point is to a musical tradition, in particular the blues tradition's impact on musical performance as a central tradition in African American culture. Indeed, this tradition of performance has had such a huge impact on the formation of African American culture that one needs some familiarity with this tradition in order to understand any aspect of African American cultural and social achievement.

Why would this be the case? Since African American history takes us back to slavery in short order, we must look to the restrictions placed on the cultural life of the slaves in order to understand the peculiarities of African American cultural expression to this day. Early in the 19th century, African American slaves were forbidden drums since its power to communicate with and between slaves was quickly discerned. Nonetheless, the essential percussive qualities of African music were taken up by all the other instruments used as well as through dance and song—work songs, spirituals to begin with and after slavery graduating to the blues and gospel. Spoken word performances, particularly epitomized by the early sermons, also extended these percussive qualities. One might say that the communicative powers of the talking drum were taken up by every aspect of African American culture.

African Americans were also forbidden religious instruction until the ecstatic religions (Baptist and Methodist) made it possible to convert the slaves without written instruction or reading since reading and writing were also forbidden. A great deal of emphasis was placed upon preventing communication between blacks on most subjects. And yet the percussive tradition, which was a communication tradition was incorporated at every level.

Granted it wasn’t possible to communicate on all subjects equally. Many have argued that folk art was always for purposes of social protest. However, it seems more likely as Albert Murray suggests, that folk expression concerned itself primarily with issues of survival and affirmation.

My Descriptive Outline of a Documentary:

Master’s of American Music----Documentary Description/Outline

Bluesland: A Portrait in American Music

Robert Palmer—Dockery Farms, early 19 hundreds a lot of important black blues players lived there including

Charley Patton who recorded a lot of music, only one picture surviving but he’s the first Delta Blues Man we can put a name to:

Son House, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters

Blind Lemon Jefferson—Black Snake Moan—East Texas

Albert Murray says herein the most distinctive thing about blues music (idiom) including jazz or any aspect of it is its emphasis on percussive statement, from its idiomatic source. Or as he calls it, the African derived disposition to use all instruments as if they were extensions of an African talking drum. So the music is incantatory and percussive.

Examples:

Bukka White--Parchman Farm Blues

Son House—The Death Letter Blues, The Pony Blues

Big Blue Broonzy

W.C. Handy—

First time he heard the blues was in Tutwiler, Miss.

Singing “When the Southern crossed the Dog,” totally knocked him sideways

Father of the Blues Industry

Closer to Ragtime—3 or 4 different strands more like a march rather than a folk song

Handy made this music readily available, put it in the public domain by analysing what was happening: The Memphis Blues, Beale Street Blues

Musical Performances:

Tommy Johnson

New Orleans

Tradition of European music interwoven with the African percussive tradition

King Oliver, Buddy Bolden—several bands

Barrelhouse Piano Blues—all the piano blues that was developed in the lumber camps from East Texas to Louisiana up through Mississippi (developed in Kansas City and Chicago); Albert Ammons; Meade Lux; the great Jelly Roll Morton from New Orleans; Little Brother Montgomery; Roosevelt Sykes

We’re talking about art, and therefore artificiality, and as such it has its own context. We’re concerned with the blues being presented always in performative contexts. Another set of conventions and traditions. The tradition of the performing artist. Style as exemplified by:

Bessie Smith—doing WC Handy’s St. Louis Blues (1929) in the only film of her directed by Dudley Murphy, accompanied by the Hall Johnson Choir.y

Ma Rainey—August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom; Boll Weevil Blues--

Ethel Waters and Mamie Smith

Race Records in the 20s made blues commercially available, although usually watered down.

Louis Armstrong's The West End Blues; Duke Ellington's Koko

Note: The Women asked me about the women. I mentioned Etta James, Big Mama Thornton, Koko Taylor and Tina Turner as people who have footage that could be easily included here except that this is easily one of those films that regards the blues as something that is mainly about the men and a few very special women (i.e. Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey). It is hard to fit all this stuff in, and then the four women who are included are all somewhat later. Still hot though!

Labels:

the Blues

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

I am a writer and a professor of English at the City College of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. My books include Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979), Invisibility Blues (1990), Black Popular Culture (1992), and Dark Designs and Visual Culture (2005). I write cultural criticism frequently and am currently working on a project on creativity and feminism among the women in my family, some of which is posted on the Soul Pictures blog.

How Music Inspired the Civil Rights Movement

Still working on this but thought we might like to have something with some of the names etcetera on it, just in case you don't know anything about these people or this music or the events being described because it would help if you did. I can see now that this is very much the perspective (or at least very useful in putting this section together with the history) of the Vernacular Section in the Norton Anthology of AFrican American Literature. And of course the Norton Anthology of African American Literature (2nd Edition) is the only one that remains out there in print because it has the bucks (editors Henry Louis Gates,Jr. and Nellie McKay) to cover most especially the rights for the speeches and the music to go with the literature. This book comes with two audio cds of both spoken word and music together with a large section on "vernacular culture" edited by Robert O'Meally. It's not perfect but it is very very good for what is required here.

I am using this massive book both in my Advanced Survey of African American Literature next semester at the City College of New York (mwallace@ccny.cuny.edu 212-60-6367), Department of English both in my Advance Survey of African American Literature and in my intro level course Blues People and Afro-American Culture Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3:30 to 4:15 and 5 to 6:15 respectively. Both courses will now begin with the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence and make stops in the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow Era, Civil Rights and Black Cultural Nationalism/Black Powerbecause these days you can't afford to leave anything to the imagination.

Let Freedom Sing: How Music Inspired The Civil Rights Movement

Time Life 2009

With all its deficits this doc is currently essential viewing in my analysis.

The Staples Singers, Bob Marley, Curtis Mayfield, Five Blind Boys, James Brown, Billie Holiday, Marvin Gaye, Hugh Masekela, Aretha Franklin, Public Enemy, Chuck D

First Music: Mahalia Jackson--"I'm On My Way"

Jackson was an extremely important person in the Civil Rights Movement and To Martin Luther King Jr. Her "Soon I Will Be Done" (which she delivers in the penultimate moment in the 1959 version of Imitation of Life) is included in the Norton anthology and on the cd. She had always wanted to be a minister herself and comes completely out of the tradition in which a solo gospel singer especially is actually also preaching a sermon and pursuing a ministry. Jackson on her own functioned much like a travelling minister (she liked to get paid in cash, put the money and her bra and drive herself to and from gigs in her Cadillac) Her heir apparent who doesn't rate inclusion in such a film as this is her heir apparent and contemporary who wasn't nearly as famous but who won the MacArthur Marion Williams and died in relative poverty and obscurity. So the diva-dom that she inaugurated lasted precisely one generation, and yet she stirs up so much resentment for her many unwise recording and business decisions. Water both under and over the bridge I think..

It is my view that the true importance of such women to the Civil Rights Movement has been buried and this film, which primarily celebrates the Movement from the perspective of the men--doesn't do much to change that.

The thing you have to remember is that nothing at all can be done with the music without copyright permissions and money. Also, since many of the people are still alive and/or their estates are still active, only very precise kinds of observations are welcome about their participation and their lives.

In this film, you are not going to find out what happened to Sam Cooke, or what happened to the Impressions, or what happened to Otis Redding, or what happened to Marvin Gaye.

The one thing it does do is that it finally sets us right about the importance of the women who sang at the March on Washington in 1963 (even though no woman got to speak it seems a lotta women sang!) and the importance of that March in general to what would follow, although there were perhaps "three minutes" of it included on the floor at "For All The World To See" at the ICP and I am not sure how much total footage of it there is here, it is always being used for different things.

Also increasingly clear to me that it was important whether you regarded events from the North or the South. Another thing about the March in 1963: heavily supported by the Unions, in particular the United Auto Worker's Union (my stepfather's union as it happens. Mom has a funny story about her and Dad driving a friend to the bus station to go to the march, somebody from his job, and everybody laughing at him all the way there because they were Malcolm X afficionados and considered King's message misguided).

What I remember was that we watched it all day long. I know there's a lot of film and more importantly that it survives. Apparently somebody rigorously controls the rights to see most of it--and sells it to the highest bidder: not sure whether it is CBS or the King hierarchy or some combination. Feels like the auction block all over again to me. That's my history.

I'd like to see that March again. All of it. Just a thought but I know it is not commercially available in any form. But I just want to say that this would be comparable to a situation in which you couldn't get dvds or video of Shoah or the Nuremberg Trials or the trial of Adolph Eichmann in Israel in the early 60s. This March was absolutely a crucial turning point. I was nine years old at the time.

Narrators discussants:

Lou Gossett--Jerry Butler, Quincy Jones, Gladys Knight, Andrew Young (former United States Ambassador and central figure in MLK's immediate circle.Billie Holiday Strange Fruit, Writer Abel Meerepol NY Teacher 1939Hezekiah Washington Freedom RiderRuby Dee seems quite crucial in the making of this and in the telling of this story, one of the dozen or so people who seems to be speaking in their own contemporary voices. Footage shot maybe 2007 or thereabout.Onze HorneBig Bill Broonzy substituted at the last minute for Robert Johnson who had just died at the historic Spiritual to Swing concert atCarnegie hall in 1946, part of the story of the specific alchemy of gospel, r&b, jazz and the blues, which produced the blues cultures that shaped the 60s.Louis Saton phd tells the story about black gospel radio in Memphis in the 40s:First there was this gospel show in MemphisWDAI (nothing black on the radio then) and Memphis was 40% black and there was a lot of music but the music on the radio was Rosemary Clooney and Pat Boone and such, total white bread. The show became an entirely black station.

Rodney King

Isaac Hayes

Rufus Thomas 50,000 watts due south going right into the heart of the Mississippi Delta.Radio was more crucial than television because there wasn't much television yet, especially down there.Reaching ten percent of the black population of the United States, all desperate for black music on the airwaves.Stations spread to Birmingham, Atlanta and across the country. I grew up listening to such stations. As a matter of fact, aren't they still there?Golden Gate Quartet Gospel music messages of a thinly veiled political naturePaul RobesonPaul Breines Civil rights activistFreedom rides 1960sThe Blind Boys of AlabamaCatherine Brooks, Freedom RiderThe Harmonizing Four "I shall not be moved"

In a demonstration at a theatre in 1960 in Nashville a man threatened to put a cigarette out in her face. She was a girl but he saw no fear. In her heart was the song "I shall not be moved."JAmes farmer, President of CORE

initiated freedom rides of the 1960s, extremely violent.

The Impressions--People Get Ready

Booker T. and the MG's

Berneice Johnson Reagon and Pete Seeger part of the translation of gospel to protest. Stax Records made r&b with movement messages: Otis Redding did A Change Is Gonna Come, written by Sam Cooke who never had a chance to hear it in release. Isaac Hayes.

Harry Belafonte--one of the first performers to get heavily involved in the Civil Rights Movement (don't know why there is a hierarchy and would like to see the timeline--surely he did more but he wasn't the only one. How about Odetta and he just couldn't be earlier than Nina Simone.) Belafonte recorded Civil Rights Protest songs. Whatever he was doing Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela were right there. Where else was Makeba going to be? After she did that first tour with Belafonte (1960?), she couldn't even go home to South Africa. Her passport was cancelled. Suspicious of the first and the most and all of that.

Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan--The Times They Are A Changing.

The Staple Singers were in the early group of the Civi Rights Movement (early or later than Belafonte?) Not sure.

Really my impression was that once things got rolling everybody who could get there was there (so far as the music if not on the actual marches. The marches were dangerous!)