|

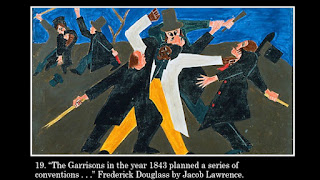

| Painting from Frederick Douglass Series (1939) by African American Artist Jacob Lawrence. Copyright restricted. See http://www.jacobandgwenlawrence.org/artandlife04.html |

There are many things that struck me as extremely relevant to our current curriculum. It helps in this case to read some of the better reviews, which may help to draw your attention to the more important historical features. I will make a folder of some of the links and place them among your course materials.

In regard to the first question I posed, that is whether it would be a reconciliationist, white supremacist or emancipationist version of the Civil War, it seemed to me that the film touched equally upon all three and ultimately did not resolve itself in favor of any of the three. In this sense, it was a fascinatingly wise contemplation on the legacy of the life of Abraham Lincoln, the conclusion of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment. But if I had to choose one, I would choose emancipationist in the sense that everything in the film pointed my thoughts to the future we actually live in, in which we have now a black president who is having as much trouble getting change through Congress as Lincoln had in having the 13th Amendment passed.

The film is about the difficulty of the political process as it occurs in a republic in which freedom of thought and word is a founding assumption. In the scene near the end of the film in which Thaddeus Stevens and his mistress Lydia Davis are reading the 13th Amendment in bed, this is where D.W. Griffith's white Supremacist film The Birth of a Nation (1915) actually begins. Both Stevens and Davis are horribly caricatured in his film and portrayed as monsters determined to destroy the country and the white majority in favor of the mongrel ambitions of miscegenation and racial mixing. Lydia in particular is demonized. It seems all the more fitting that Spielberg's film would end with Lydia humanized by the sensible acting of Epatha Merkinson, whom we have all known so many years from Law and Order. I don't think the part is big enough for an actual nomination but I wish it were.

As for the reconciliationist perspective of a film such as Gone With The Wind (1939), the profound depth and tenderness of the mature relationship between Lincoln and his wife Mary seems to mock the trivial superficiality of such a treatment of the Civil War and hits consequences. Abraham and Mary's contrast with Rhett and Scarlett couldn't be greater or more revealing.

What makes it such a great lesson for all of us is that it brings the legislation we have been studying vividly to life. I don't think you can come away from watching this film without becoming completely cognizant of what the 13th Amendment achieved (the abolition of slavery), or how it differed from the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as its limitations and ultimately the necessity for both the 14th (citizenship) and the 15th (the vote)Amendment. What is forecast as well, it seems to me, is that none of this legislation would finally succeed in transforming the former slaves into fully recognized and fully participant American citizens.

The portrayal of events takes for granted the omniscience of white supremacy at the time. The very fact that Congressman Thaddeus Davis, who is in a relationship with a black woman to whom he takes the rough draft of the amendment to read to her in bed, is forced to renounce his own beliefs in racial equality on the floor of the congress in order to get the 13th amendment passed clarifies the hegemony of white supremacy at the time. Nonetheless, it further embellishes one's enjoyment of these events if one knows what will follow--as you can easily find out by reading, first of all, the second chapter of W.E.B. Du Bois's The Souls of Black Folk (which you have already been assigned to do), not to mention as well the Reconstruction Wiki I assigned you.

Which brings me to the only disappointment I felt in this film and that is that there are no roles for blacks large enough to get your teeth into, not even that of Nancy Keckley who was Mary Lincoln's dressmaker and companion. All of the black roles--in particular the soldier in the beginning who completes the recitation of the Gettysburg Address as he wanders off into the night--are lovely and beautiful but they are not allowed to take on important dramatic depth and substance. Perhaps it wouldn't be appropriate to this portion of the history, the month or so preceding the murder of Lincoln, and it seems petty in the end to quibble about this one shortcoming when so many other films in which black actors are featured have none of the pluses of this beautifully and densely written script, but it is hard to believe that this isn't an important consideration. If it isn't important, why not have the densely written black character instead of not?

To which I have two perhaps contradictory answers. First, part of the reason it is this way is because of the evils of the star system, and the fact that the name brand combination of the package takes precedence over whatever magic the script and the performance are able to produce. It's got to be an exciting package from the marketing point of view. Nothing else matters. Even so I can't imagine that this film will do particularly well at the box office but it should do very well indeed among the awards.

Just look at the content of the advertising, the focus on the tortured face and figures of the stars--Daniel Day Lewis and Sally Fields--both wonderful but without their former reputations as actors, they would not be able to occupy these roles. Not as unknowns. Which also means the following. First of all no black woman could be given a major role. Black actresses just aren't there yet. Not even Haile Berry. Not even Vanessa Williams. Rather it would have to be a black male with a major name, and such a man (Denzel Washington or Sam Jackson or somebody like that) would never take the lesser role that such a part would likely be. A major black male role would be in danger of completely derailing the subtle balance of the current script. This film is not about the freedom or the equality of women or of blacks, but rather a moment still pregnant with that possibility.

At the same time, the racial equilibrium of this script speaks to the ongoing power of white supremacy in our culture, to the fact that we still don't know how to imagine what kind of moral and aesthetic hierarchy might actually follow. That just like Lincoln and his most well intentioned contemporaries we still don't know quite how to incorporate the agency of actual black people (and former slaves) into the mainstream of the story we tell ourselves about the history of our country and our culture.